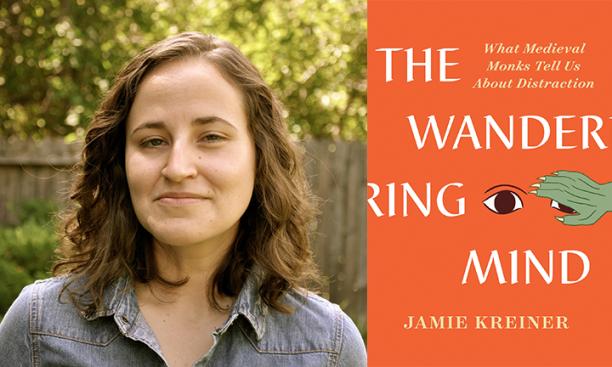

Jamie Kreiner *11’s new book, The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us About Distraction, achieved a rare feat for a scholarly work. The New York Times hailed it as “charming and peculiar.” The Wall Street Journal called it “lucid and vivid.” A feature in The New Yorker deemed it “wry and wonderful.”

“That was crazy,” says Kreiner, a historian at the University of Georgia who studies Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. “Historians of the early Middle Ages like myself usually only expect that people in our small area will read our books.”

Far from being masters of meditation, monks suffered from distraction as much as modern mortals, Kreiner found. For them, failure to focus on self-enlightenment kept them from God. She writes that some believed “demons deploy[ed] intrusive thoughts … custom-fit to their targets” while others blamed their lack of will power. Worse, they feared distraction was “primordial … the result of humanity’s initial separation from God.”

To learn how monks sought to be more mindful, Kreiner studied holy men and women who lived from about 300 to 900 A.D. in areas as far-flung as Ireland and Mesopotamia. Their remedies ranged from fasting and isolation to silence and sleeping standing up. Staying on task was often made more difficult because many monasteries were far from airtight. Many ran charities, organized festivals, and offered counseling.

Distraction, they realized, was part of being human. “Because they saw the mind as embedded in all these other systems, there was no single fix,” says Kreiner, who currently serves as Georgia’s associate dean of humanities. “They realized they needed to try to do lots of different things simultaneously to thwart distraction. They knew you would never solve the problem permanently. You could only improve your relationship to it.”

To help freshmen study, she has taught them “medieval cognitive practices.” Kreiner borrowed one technique from French monk Hugo of St. Victor, who lived in the 12th century. He wrote a book about his construction of a mental ark, imagining each of its planks, beams, and compartments permitted infinite intellectual storage capacity like hard drive folders.

“For students, it could be building a solar system to think about organic chemistry, a city block to think about conjugations in Latin, or a massive hotel for a marketing exam,” she says.

Kreiner wrote her dissertation under Peter Brown, the Princeton history professor emeritus who is widely considered to have founded the study of Late Antiquity. “He taught me how to listen carefully to what the sources were saying,” she recalls.

After taking her post in Georgia, Kreiner received a yearlong fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study, where she wrote her book Legions of Pigs in the Early Medieval West. “Being there let me concentrate on my research constantly. It was crazy how much you can get done in an environment like that,” she says.

Being focused hasn’t always been easy for her. When she was an undergraduate at the University of Colorado-Boulder, her clarinet professor taught her how to best manage her time in practice rooms. “He was, like, you can get a lot done if you’re watching yourself and notice immediately when you zone out. Then you can make conscious choices about why you’re practicing and respond to your inner feedback right away.”

When asked if stray thoughts harass her, Kreiner insists she is the master of her mind. “I don’t get distracted easily,” she says. “I say ‘no’ to a lot of things, so my plate isn’t too full. I also stick to a schedule pretty closely and do my hardest work in the morning before the day gets cluttered.”