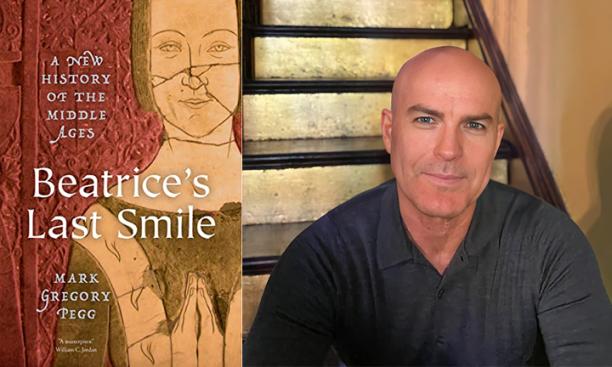

Sweeping narrative histories are “the inescapable background music to our research and writing,” scholar Mark Pegg *97 writes at the start of his most recent work, Beatrice’s Last Smile: A New History of the Middle Ages.

Pegg, a professor of history at Washington University in St. Louis, focused on heresy, the medieval inquisition, and the 13th-century crusade against Christians in southern France in his first two books, but in his third he took up the challenge of telling the story of the West between 200 and 1400 A.D.

“There has been a tendency that historians no longer write these books despite the fact that there’s a huge audience for them outside the academy,” Pegg says. “I thought it would be fun to write a synthetic book that could be read by scholars and ordinary readers. These works help society more generally — especially outside the academy — understand the past.”

Pegg takes the title of his book from the final scene of Dante’s Divine Comedy, in which Dante’s beloved Beatrice smiles at him one last time before she turns away. Earlier in the poem. Beatrice warns Dante that her smile will incinerate him. The exchange “evokes the ebb and flow of holiness and humanity in the living of a life, whether on earth or in heaven (or in hell or in purgatory) that shaped the medieval world,” Pegg writes in the book.

Pegg says that he liked the image even before he started writing Beatrice’s Last Smile. “I had always thought it would make a great title and a shaping image for a book on the Middle Ages,” he says. “There was a sense that I was writing to get to that point and then moving away from it.”

Managing more than a millennium’s worth of material was challenging, Pegg says. He took inspiration from two books written by professors with whom he studied at Princeton: The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200-1000 by Peter Brown, and Europe in the High Middle Ages by William Chester Jordan *73, who was Pegg’s dissertation adviser.

Jordan’s work, Pegg says, encouraged him that “a book covering a great temporal swathe could be learned, insightful, and written in a narrative brimming with wit and elegance.”

Getting there wasn’t easy, though. “I would be foolish to deny that there were some chapters I began, and I had no idea where I was going,” Pegg says, though he found his footing by the third of his 10 chapters. Pegg also discussed his work often with Randall Pippenger *18, a student of Pegg’s at Washington University who went on to study with Jordan at Princeton.

“I chose a certain style in which to construct the narrative by trying to piece together many different people,” Pegg says. He starts and ends the book with Christian martyrs; Vibia Perpetua “was ritually murdered by gladiators with swords” in a Roman amphitheater in Carthage in 203, while Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in Rouen, France, in 1431.

“I wanted the reader to get a sense of the beauty and grandeur of the medieval world as well as its cruelty,” Pegg says. “That’s why I like the Beatrice metaphor and her last smile. There’s a holiness infused with a kind of violence, a combination of beauty and terror that has always been very much the Middle Ages for me.”